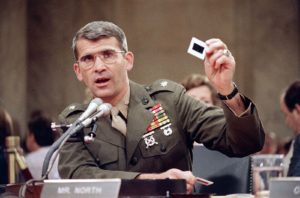

Twenty-five years ago, in February of 1989, Oliver North stood trial on 12 counts related to lying to Congress about his role in the Iran-Contra Affair.

One of the most damning pieces of evidence that had led to North’s trial was his own email. Specifically, emails that Oliver North and John Poindexter thought they had deleted from their computers at the National Security Council. Unfortunately for them, the email server in the White House kept archives of all sent and received email. The deleted emails became evidence for the committee investigating the Iran-Contra affair and subsequent trial. The emails also were used by the Tower Commission and by the Department of Justice in connection with its prosecution of Manuel Noriega.

25 Years is a Long Time…

I’m sure someone will disagree with fixing the origins of eDiscovery to that one trial 25 years ago. I’m sure that electronic evidence was prominently featured in other legal matters before this one. (And let’s be honest, editors love arbitrary anniversaries as a hook for stories. (Editor’s Note: You’re right! I love it!))

But the bottom line is that eDiscovery is now a very old and very established part of litigation. A quarter century ago, email and computer forensics were central to one of the most high-profile and important trials of the decade. Yet some lawyers still think of digital evidence as an afterthought. (And some lawbreakers still think they can delete evidence.)

…Get over It!

Lawyers still fail to take eDiscovery seriously and still get in big trouble for it. In the recent case Pradaxa Prods. Liab. Litig., MDL No. 2385 (S.D. Ill. Dec. 9, 2013), the court punished defendants for failing to preserve electronic evidence. That included a failure to implement a litigation hold strategy, resulting in sanctions for responding to the court’s case management orders in bad faith.

Listen, it’s now 2014 and a legal team’s duty to preserve has been spelled out in case law for more than a decade. Even worse, the court in the matter had issued explicit instructions for the production of relevant documents or an explanation regarding why they could not be produced. That’s why the defendants are now paying the Plaintiffs’ Steering Committee’s (PSC) discovery costs and fees and must now produce their employees for depositions. The court also imposed a fine of $931,500 jointly and severally against both defendants ($500 per case).

The court broke down the failure into four categories:

- The failure to timely identify as a custodian a “high-level scientist that worked on Pradaxa and published articles on Pradaxa as a lead author.”

- Failing to put an adequate litigation hold in place for Pradaxa sales representatives until over a year after the duty to preserve was triggered.

- The failure to provide passwords and access to shared networks and electronic files.

- Ignoring text messages and other potentially pertinent records, allowing “countless records to be destroyed.”

The court found that each failure constituted a violation of the court’s case management orders and was in bad faith. “Almost since its inception, this litigation has been plagued with discovery problems primarily associated with misconduct on the part of the defendants,” according to the ruling. The defendants in this case are certainly not guilty of lying to Congress or shredding documents in their office with Fawn Hall. But destroying records, failing to produce evidence, and failing to identify custodians or put litigation hold orders in place are unforgivable actions in eDiscovery. Especially 25 years after one of the most high-profile cases in American history made much of this clear.

[hs_action id=”6358″]